From Analogue Libraries to The WELL, Wired, WordPress, to Substack

Between Stories

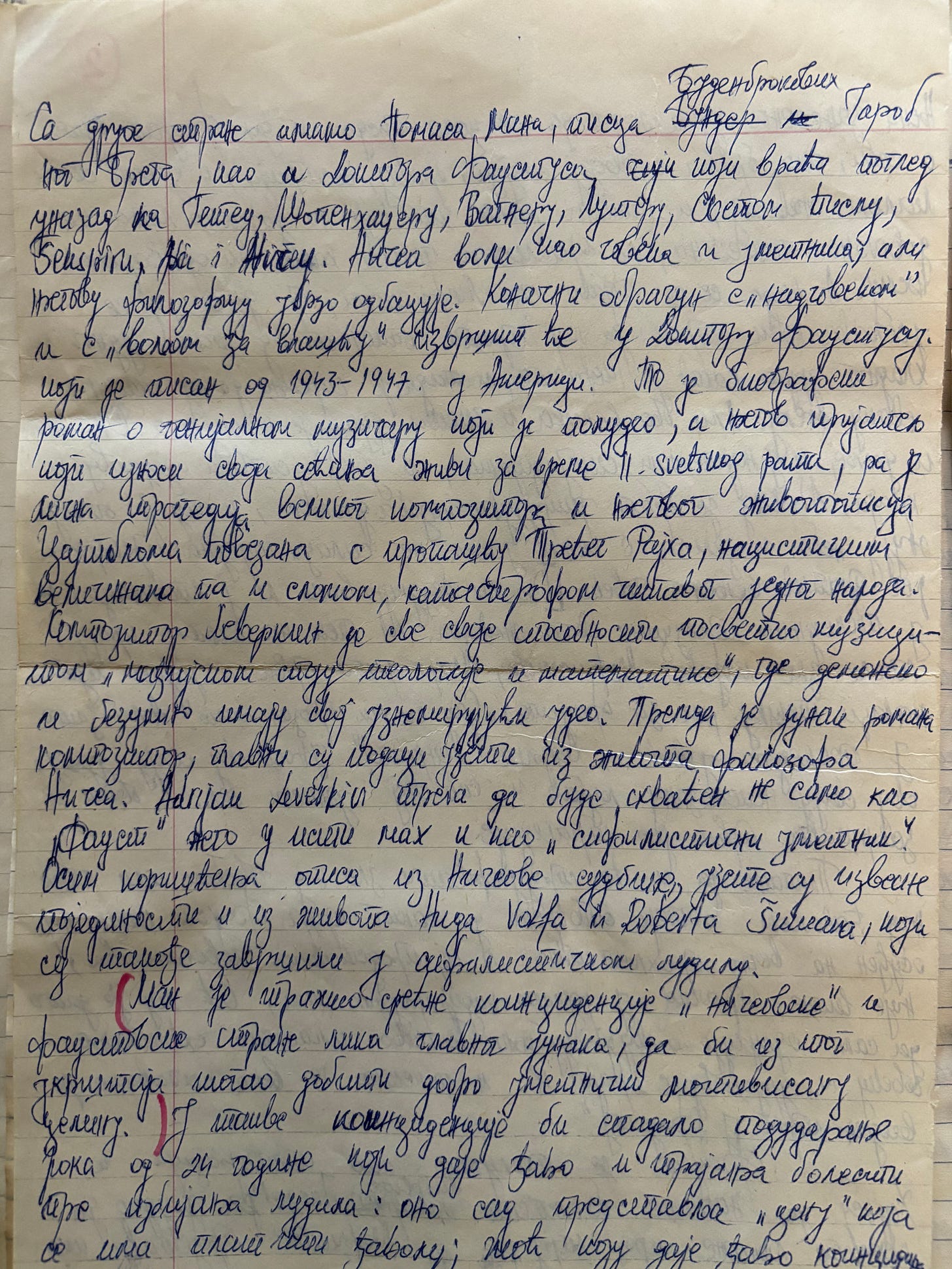

The other day, while revisiting my own library, I came across one of my earliest writings, a paper essay from high school, covered in my teenage handwriting. A critical literature essay, full of humor, intensity, and the audacity to connect books across centuries. Holding those pages, I thought: did I really write this? Wow… so this is how it all started.

When I think about my earliest days as a writer, I return to a dimly lit public library in the 1990s in Yugoslavia, when the world outside was collapsing, but the world inside the pages of books was infinite. We did not yet have the internet. We had only shelves, dust, and stories. And books saved me.

I grew up surrounded by books, in a family where reading was almost a second language. Our “family library” was not one library but several: three clusters of shelves, each carrying its own voice. My mother, a professor of Russian language and literature, filled hers with Russian classics in the original, alongside critical works and poetry. My father’s library was another world: musicology, sociology, media studies, phenomenology, French critical thought. And then there was my own collection, stitched together from school readings, translations, philosophy, religion, and discoveries. To move through these shelves was to move through a cornucopia of ideas.

While others of my generation might have wandered the early internet (when it finally reached us in the late 1990s), my adolescence was spent in the physical library, flipping through catalogs, pulling volumes from stacks, reading entire shelves if I could. That was my internet. My search engine was curiosity. And inevitably, if you are an avid reader, you will eventually become a writer. It was the natural course.

One memory stands out: the semester I read Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann alongside Goethe’s Faust, while simultaneously delving into Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov. I attempted a triple comparative analysis, Mann’s modern despair, Goethe’s striving, Dostoevsky’s moral torment. What ran through all three was a single thread: the cost of knowledge and the ethics of desire. Reading them together felt like building a dialogue across centuries, one that still echoes in how I approach texts today.

Later, at university, my writing widened. I published essays and reviews on literature, music, film, and soon short stories of my own. Some found their way into anthologies of contemporary urban writing, my first tangible recognition as part of a literary generation.

But as the millennium turned, something shifted: my words migrated from paper to the digital screen. I co-founded (with friends in Belgrade) ArtArea, the first electronic magazine in the region, and became its editor-in-chief, covering literature, architecture, and design.

Soon after, in the early 2000s, I launched one of the very first blogs on Wired and later Blogspot. Among the earliest voices from the Balkans to join that platform, I treated it as a red-lit digital diary: dispatches from both coasts of America, fragments of life, reflections, and stories.

By 2007, my voice found another home on WordPress, where I created the long-running blog Belgrade and Beyond. For many years, it became a cultural chronicle and personal anchor: essays, photographs, stories, and fragments of life and internet as a medium that tied my city to the wider world.

Parallel to this, in the late 90s and early 2000s, I entered into a larger digital community. I was among the first voices from the Balkans to join The WELL, that legendary virtual space where writers, thinkers, and early digital visionaries gathered. There, as a young female scholar and student, I exchanged ideas, thoughts, and early writings with older participants, pioneers of the internet age. The WELL was a hub of conversation: Howard Rheingold was an active member whose The Virtual Community shaped how we think about online life; John Perry Barlow and others tied to the Electronic Frontier Foundation brought the urgency of digital rights and free expression to its forums. The WELL even hosted a vibrant “Grateful Dead” conference, showing how countercultures and fandoms could find a home online.

For me, The WELL was a revelation. To sit at the same table, even if virtual, with writers, activists, and thinkers from across the world was transformative. It was my first glimpse of what global dialogue could be. Soon after, I began publishing in Wired and other early platforms, exploring how digital culture was reshaping the way we write and think, while also establishing myself as an internet scholar.

It was also where I met Americ Azevedo, the “philosopher-at-large” from UC Berkeley, who became a dear friend until his passing in 2019. Americ embodied dialogue: weaving philosophy, technology, and meditation into every exchange. Our conversations about presence and connection left a lasting imprint on how I understand digital community. Around the same time, I encountered Paul Jones, director of ibiblio.org, a pioneer of digital libraries and open knowledge, whose work in preserving and sharing information embodied the internet at its most generous. Paul later became my mentor during my time at the UNC postgraduate scholarship, and we remain friends to this day. He has visited Belgrade several times, and his son Tucker developed a love for the Balkans, carrying forward that spirit of connection across generations.

Over the years, I have written in numerous magazines, journals, and books on digital media, technology, digital inclusion, and critical theory, work that bridges my early literary roots with the questions of the digital age.

Looking back, I see a continuity rather than a break. From family libraries to global networks, from handwritten notes to blog posts, from journal essays to digital scholarship, the medium shifted, but the impulse stayed the same: to read voraciously, reflect critically, and write into the world.

If there is one lesson I carry from those paper essays in the 1990s to this Substack today, it is this: words still make worlds, but even more, it is our stories that keep us alive. Across centuries, we have survived by telling ourselves and telling each other stories. In speaking, in writing, in exchanging them, we connect.

So here I am, once again, writing “in between stories” . A new home, but also a return, to that same young reader in the library, to the adolescent who believed in the power of literature to transform a life. And to the belief that even now, in pixels and paragraphs, our stories still carry that power.